So Many Stories

by Katy Wimhurst

Magical Realism and History

Traditionally, history and literature have been seen as quite different domains, the former based on facts, evidence, the latter pertaining to the realm of fiction, invention. However, recent thinking, particularly that associated with postmodernism, has questioned the absolute divide between fact and fiction, arguing, for instance, that history may itself be a type of fiction—a set of stories told by certain (often dominant) social groups with their interests and self-image in mind—while literature can embody 'alternative' histories.

Traditionally, history and literature have been seen as quite different domains, the former based on facts, evidence, the latter pertaining to the realm of fiction, invention. However, recent thinking, particularly that associated with postmodernism, has questioned the absolute divide between fact and fiction, arguing, for instance, that history may itself be a type of fiction—a set of stories told by certain (often dominant) social groups with their interests and self-image in mind—while literature can embody 'alternative' histories.

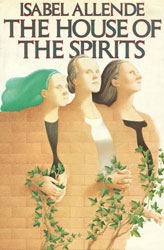

Such ideas are particularly relevant to magical realism, a literary genre in which many classic works come from outside the west, the global centre of cultural power, and allude to significant historical events and periods, albeit in an idiosyncratic manner: Isabel Allende's The House of the Spirits (1982) is set against the 20th-century history of a country easily identifiable as Chile, including the brutal military coup of 1973. Salman Rushdie's Midnight's Children (1981) is an inspired exploration of modern India, particularly during the first thirty years of the Indian State (1947-78). Gabriel García Márquez's One Hundred Years of Solitude (1967), the seminal work of magical realism, is said to be a rewriting of the history of rural Columbia (or of rural Latin America more generally), while his The Autumn of the Patriarch (1975) is the life and death of a dictator who is between 107 and 232 years old, a fictional amalgam of a number of real autocrats from Latin America and Europe. Alejo Carpentier's The Kingdom of this World (1949) reconstructs the black slave revolt in Haiti in the 1800s. Toni Morrison sets out to recuperate the historical experiences of African-Americans in her novels, especially in relation to slavery.

Although the meaning of 'magical realism' is debated, it broadly refers to stories which incorporate magical elements into a predominantly realist narrative. When magical realism refers to actual historical events, this never eclipses the quixotic stories of individuals caught up in them, and the narrative weaves seamlessly between the realms of the historical and the imaginative. In One Hundred Years of Solitude, Colonel Aureliano Buendía, a Liberal rebel, is the character who comes closest to resembling a real person from Columbian history, but the rendering of the man's life shows García Márquez at his most appealingly extravagant:

Colonel Aureliano Buendía organized thirty-two armed uprisings and he lost them all. He had seventeen male children by seventeen different women and they were exterminated one after the other on a single night before the oldest one had reached the age of thirty-five. He survived fourteen attempts on his life, seventy-three ambushes and a firing squad. He lived through a dose of strychnine in his coffee that was enough to kill a horse. (p.106)

The central narrator of Midnight's Children, Saleem Sinai, is also an extraordinary figure, possessing telepathic skills as well as a huge, eternally dripping but deeply sensitive nose, one which enables him to identify "the perfumes of . . . ideas, the odour of how-things-were" (p.592). Saleem describes himself as both 'fathered by' and 'handcuffed to' history: along with a thousand other babies, he is born at midnight on the date that India achieves independence from British rule, and the thirty years of his life are "a microcosm of the course of the Indian state (1947-78) from Independence to Emergency" (Merivale 1995: 330). Saleem engages in the deliciously phrased 'chutnification of history': just as he oversees the pickling of fruit in jars during the day, so he preserves a personal account of his—and (incidentally) India's—history in his nocturnal writings. He reads this personal history aloud to his wife-to-be Padma, who comments on it, often in an amusingly curt manner—in Chapter 2, for instance, she exclaims, "What is so precious . . . to need all this writing-shiting?" (p.24). Saleem loses his telepathic abilities during the course of the story and by the end, in a way that symbolizes the dissolution of the Indian state, his body, 'buffeted too much by history', is impotent and literally falling apart.

When magical realism includes historical references, this is not simply to reinforce its realist credentials or to situate a novel in a particular time and place. The works take playful license with the rendering of history, showing how they are imaginative reconstructions which unsettle western conventions of realistic representation and draw, for instance, on the story-telling techniques of non-western (and non-rational) traditions. García Márquez is known for being influenced by the fabulous oral story-telling of his Columbian grandmother, who taught him 'the extraordinary was something perfectly natural', while Midnight's Children recalls the orally-recounted Arabian folk tales, One Thousand and One Nights, a work Rushdie's (postmodern) novel alludes to in various ways. In a manner that deftly echoes Rushdie's own narrative style (and that of magical realism more broadly), the character Saleem talks about, "Matter of fact descriptions of the outré and bizarre, and their reverse, namely heightened, stylized versions of the everyday" (p.303). Rushdie has commented that how people respond to his book actually depends on their cultural background: "In the West people tended to read Midnight's Children as fantasy, while in India people thought of it as pretty realistic, almost a history book" (2005: xvii).

Just as magical realism may be inspired by non-western narrative styles, it also often embraces the folk wisdom and magic of the non-west, sometimes in a playful or 'knowing' manner, sometimes more sincerely. "Texts labelled magical realist draw upon cultural systems that are no less 'real' than those upon which traditional literary realism draws--often non-western cultural systems that privilege mystery over empiricism, empathy over technology, tradition over innovation" (Zamora and Faris, 1995: 3). García Márquez's comment that what seems fantastic in his fiction is actually real, needs to be understood in the context of his assimilation of Latin American folk culture, with its mythic ways of seeing, into a literary style that has been labelled as modernist or postmodernist. And Alejo Carpentier (1949) has suggested that the marvellous quality of (what is now termed) magical realism is simply the amplification of 'the marvellously real' he sees as intrinsic to the history and culture of the Americas. The belief among black people of the Americas that individuals can fly, including back to their homeland of Africa—a belief that originated during the era of slavery but continued after its abolition—features in Carpentier's The Kingdom of this World as well as in Morrison's Song of Soloman (1977). Towards the end of Song of Soloman, for instance, the central character, Milkman Dead, tells a lover how his great-grandfather escaped an oppressive slave life by simply flying away:

Oh man! He didn't need no airplane. He just took off; got fed up. All the way up! No more cotton! No more bales! No more orders! No more shit! He flew, baby. Lifted his beautiful black ass up into the sky and flew on home. (p.328)

Magical realist books tend not to judge the veracity of such magical events and therefore validate magic and myth, seeing these as legitimate ways of relating to the world, as acceptable systems of collective meaning. A book like Song of Solomon, which includes people flying, a woman without a navel and dead people who talk, tries to recuperate the forgotten or subsumed histories of African-Americans, but in a way that acknowledges the supernatural beliefs of such people. In telling stories from the perspective, and in the vernacular, of those whose experience and world-views have been marginalized, Morrison gives voice to the dispossessed and recognizes how political power is not just the power to govern but to name, to speak and to be heard. Her books fill a gap in African-American cultural memory, preserving "pasts often trivialised, built over or erased, and pass[ing] these on" (Foreman 1995: 286).

Magical realist works can thus offer "alternate versions of officially sanctioned historical accounts" (Faris 1995: 170). But they do so with an imaginative profusion that stops them descending into gauche protest novels, that acknowledges their status as art/entertainment, and that recognizes how historical experience itself is messy and ambiguous. The Canadian literary critic Stephen Slemon (1995) suggests that, going against the traditional style of imperialist/western history, which focuses on monumental achievements and pedals linear accounts from the perspective of the powerful, magical realism succeeds by telling history in diverse, often contradictory, voices. In relation to colonial or postcolonial countries, Slemon values stories that include magical and realist narrative elements which (he argues) (i) constantly struggle against one another, each trying to become 'the language of truth', and (ii) allow events to be told from (at least) two perspectives: that of the colonised and the colonisers. In Alejo Carpentier's The Kingdom of This World the slave revolt in early 19th-century Haiti is conveyed from the viewpoint of both African slaves and European masters. At one time, the character Bouckman, a voodoo priest and instigator of the rebellion, gathers the other slaves together at night at a clandestine voodoo ceremony to prepare for the coming struggle. It is clear this is perceived as a fight with mythic dimensions:

[Bouckman] stated that a pact had been sealed between the initiated on this side of the water and the great Loas [deities] of Africa to begin the war when the auspices were favourable. And out of the applause that rose about him came this final admonition:

'The white men's God orders the crime. Our gods demand vengeance from us. They will guide our arms and give us help . . . let us listen to the cry of freedom within ourselves.'(p.40)

A few pages later the revolt is seen from the point of view of the slave plantation owner, Monsieur Lenormand de Mézy, who hides during the rebellion and eventually emerges to find his house destroyed and his wife murdered. He hurries to the safety of the town of Cap Français where he meets the French Governor, who says a word he has never paid much heed to before: voodoo. Monsieur Lenormand de Mézy realises that:

The slaves evidently had a secret religion that upheld and united them in their revolts. Possibly they had been carrying on the rites of this religion under his very nose for years without his suspecting a thing. But could a civilised person have been expected to concern himself with the savage belief of people who worshipped a snake? (p.47)

A divergence of (cultural) perspectives is also apparent in Gail Anderson-Dagatz's A Cure For Death By Lighting (1998), the story of a provincial Canadian community during the time of World War II, told through the eyes of white teenager Beth Weeks. When a local girl is brutally killed in the woods, the white community makes the 'rational' inference that a bear has caused the atrocity, but Bertha Moses, a reservation Indian, maintains that Coyote, an Indian trickster deity, is responsible. During a visit to the Weeks's home, Bertha explains her conviction, albeit in a way that is eventually ridiculed by Beth's father, John:

"[Coyote] rides on the spirit of a newborn into this world. It don't have to be a human newborn, it can be an animal, but once he's born into this world, he slips off and goes walking until he finds somebody to have some fun with, eh? He takes that somebody over, see? Possesses him, like them demons in the Bible. Coyote has an awful thirst. Can't satisfy him no how, that's what makes him so bad . . . Ain't that right, John?"

My father laughed, a long powerful laugh, and all of us watched him at it. My mother covered her face with her hands. (p.72)

The presence of diverse, even contested 'voices' is one reason why magical realist works have been seen as postmodern. Maggie Ann Bowers suggests that much magical realism follows postmodern thinking about history which "emphasises the lack of absolute historical truth and casts doubt over the existence of fact by indicating its link with narrative and stories" (2004:77). Bowers' idea finds support in Salman Rushdie's (non-fictional) comment that, "History is always ambiguous. Facts are hard to establish and capable of being given many meanings. Reality is built on prejudices, misconceptions and ignorance as well as on our perceptions and knowledge" (1992: 25). Rushdie's novels illustrate how, if history is told from one person's viewpoint, many other historical perspectives need to be acknowledged in order to approach a more coherent account of any epoch. Midnight's Children is an encyclopedic exploration of a society and era through the personal story of Saleem, who says:

There are so many stories to tell, too many, such an excess of intertwining lives events miracles places rumours, so dense a commingling of the improbable and the mundane. I have been a swallower of lives; and to know me, just the one of me, you'll have to swallow the lot as well. (p.4)

If some have emphasized the 'polyphony' of voices in magical realism, it is important to note that writers often position themselves in relation to these voices. Carpentier may include the perspective of the slave-plantation owners, but his sympathy ultimately lies with the slaves; Anderson-Dagatz's book includes white and Native American voices, but by the end, Beth Weeks accepts the latter's version of events; Midnight's Children is perceived as a postcolonial alternative to imperial accounts of Indian history; and Allende's The House of the Spirits may offer no authoritative account of Chilean history, but it positions itself against the ruthless military (Pinochet) dictatorship that seized power in 1973 (Isabel Allende is the niece of Salvador Allende, the democratically elected left-wing president who died, among with many others, during Pinochet's coup).

Toni Morrison has said magical realism involves 'another way of knowing things'. As with Rushdie, her writing includes the acceptance of 'the magical' together with a profound rootedness in the real world. In this way, imagination and history coexist, nurturing each other, neither taking precedence. As an author concerned with cultural memory and identity, Morrison's novels intimate that the mythic imagination is as important to these as historical 'facts'. If (following postmodern thinking) history is ultimately a type of fiction, then fiction like magical realism could be a type of history, albeit one that, reveling in its imaginative excess, acknowledges its fictitious nature.

References

Bowers, Maggie Ann (2004), Magic(al) Realism, London:Routledge.

Carpentier, Alejo (1949) 'Prologue to A Kingdom of This World', reprinted in Zamora and Faris (1995) Magical Realism: Theory, History, Continuity, Duke University Press.

Faris, Wendy (1995) 'Scheherazade's Children: Magical Realism and Postmodern Fiction', in Zamora and Faris (1995) Magical Realism: Theory, History, Continuity, Duke University Press.

Foreman, P. Gabrielle (1995) 'Past-On Stories: History and the Magically Real, Allende and Morrison on call', in Zamora and Faris (1995) Magical Realism: Theory, History, Continuity, Duke University Press.

Merivale, Patricia (1995) 'Saleem Fathered by Oskar: Midnight's Children, Magic Realism and The Tin Drum', in Zamora and Faris (1995) Magical Realism: Theory, History, Continuity, Duke University Press.

Rushdie, Salman (1992) Imaginary Homelands: Essays and Criticisms 1981-91, London: Granta.

Rushdie, Salman (2005) 'Introduction', Midnight's Children (2005) [1981], London: Vintage.

Slemon, Stephen (1995) 'Magical Realism as Postcolonial Discourse', in Zamora and Faris (1995) Magical Realism: Theory, History, Continuity, Duke University Press.

Zamora, Parkinson Lois and Faris, Wendy (1995) 'Introduction; Daiquiri Birds and Flaubertian Parrot(ie)s', in Zamora and Faris (1995) Magical Realism: Theory, History, Continuity, Duke University Press.

Story Copyright © 2007 by Katy Wimhurst. All rights reserved.

Previous: The Apparition of Mrs Veal by Daniel Defoe | Next: On looking beyond the veil by Jenni Fagan

About the author

Katy Wimhurst, who lives in Essex, UK, originally trained as a social anthropologist, but somehow ended up doing a PhD on Mexican Surrealism. She has a soft spot for magic, myth and mud. In a past life, she might have been Salvador Dali's moustache, and she'd like to be reincarnated as one of Russell Hoban's dreams. She writes fiction and non-ficion and has had stuff published in various magazines and online publications, including Guardian (Unlimited).

Katy Wimhurst, who lives in Essex, UK, originally trained as a social anthropologist, but somehow ended up doing a PhD on Mexican Surrealism. She has a soft spot for magic, myth and mud. In a past life, she might have been Salvador Dali's moustache, and she'd like to be reincarnated as one of Russell Hoban's dreams. She writes fiction and non-ficion and has had stuff published in various magazines and online publications, including Guardian (Unlimited).

Home

|

Competition

|

Privacy

|

Contact

|

Sponsorship