Magic(al) Realism

by Katy Wimhurst

A Short History of the Term

In this piece I offer a short history of the term magic(al) realism, asking how a phrase first used to describe a type of German painting in the 1920s, ended up being associated with a successful literary genre which initially had its roots in Latin America in the 1960s but which subsequently has enjoyed more global appeal. The terms 'magic realism' and 'magical realism', along with the associated one of 'marvellous realism', have all been used in connection with inspired writers like Gabriel García Márquez, Isabel Allende, Salman Rushdie, Angela Carter, Alejo Carpentier and Toni Morrison. But are these terms actually identical or do they differ in significant ways? In exploring such questions, and in trying to map out a brief history of magic(al) realism, it is important to be aware that the terms magic realism, magical realism and marvellous realism all elude simple definition and that the connections between them are complex. Anyone wanting a quick summary of their meanings could scroll down to the bottom where I give a brief overview.

'Magic realism' (Magischer Realismus) was a term first coined by the German art historian Franz Roh in 1925 to describe a type of painting that flourished during the Weimar Republic in Germany, associated with artists like Otto Dix, George Grosz, Carl Grossberg and Alexander Kanoldt. Their paintings differed significantly, from the meticulously painted urban scenes of Grossberg, to the eerie still-lives of Kanoldt, to the biting social satires of Dix and Grosz. What the artists shared, however, was a concern to produce paintings that were grounded in the objective world, yet not completely of it. The phrase 'magic realism' suggests the artworks were not meant as merely photographic-like representations. Rather, while using the starting point of real-world objects and scenes, the artists tried to tease out the hidden dimensions that lurked behind the surface of things, to offer "a magical gaze opening onto a piece of mildly transfigured reality" (Roh 1995 [1925]: 20). An important precursor was the Italian painter Giorgio de Chirico (1888-1978) who created mysterious works in which isolated objects—monumental statues, mannequins—stand immobile in deserted plazas, across which long shadows fall (see Figure 1). De Chirico's works are known for representing familiar objects from unfamiliar angles and perspectives, a quality Roh felt was present in magic realist painting too. De Chirico's paintings thus make 'the unreal seem real, the real unreal' and carry an eerie sensibility that, following Freud, has been referred to as Unheimlichkeit ('the uncanny').

Figure 1: Giorgio de Chirico, The Enigma of a Day (1914)

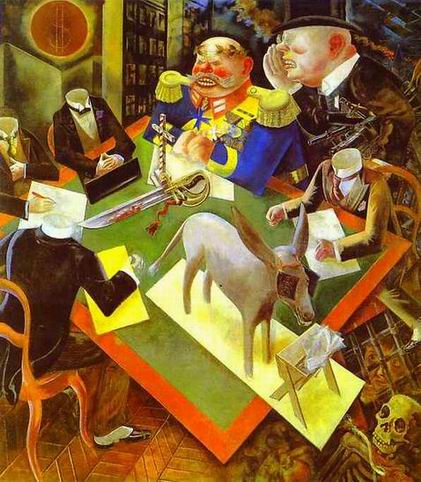

The focus of German magic realists on objects and scenes from the real world partly reflected how, in their era, 'reality' was hard to ignore. As in many Latin American countries where the literary genre of magical realism later took root, historical reality in Germany intruded into everyday life with an uncompromising brutality. The painters grew up in an era of death and destruction, the horrors of World War I haunting them. They later found themselves amidst the political and economic instabilities of the post-war Weimar Republic, with its weak government, soaring inflation and, eventually, rise of Fascism. Not all magic realists addressed historical realities directly, but Otto Dix and George Grosz offered a socially engaged art, depicting, in almost grotesque caricature, scenes from modern German life, using modernist aesthetic techniques like the distortion of form. In Dix's The Match Seller I, 1920, an amputee (perhaps a war veteran) with a face the size of his body, sits begging on the pavement, but is urinated on by a dog. In Grosz's Eclipse of the Sun, 1926 (Figure 2), an artwork the Peruvian writer Mario Vargas Llosa has said possesses qualities analogous to his own work, an oversized General sits at a table while a smartly dressed man holding a cachet of guns whispers in his ear. Around the table suited men hold pens and paper but have their heads missing; and on the table stands a blinkered mule with a manger full of discarded documents. The symbolism of the work is complex, but generally it is said to be a scathing indictment both of the powerful military-industrial complex within Weimar Germany and of capitalism/materialism more generally—the characters are assembled under a sun obscured by a dollar sign. While the fantastic elements of this work are considerably more accentuated than in much German magic realism, the picture illustrates a general feature of magic realist art: it retains a foothold in the real world whilst pointing towards a realm beyond surface appearance—in this case, a sinister one of greed and political corruption.

Figure 2: George Grosz, The Eclipse of the Sun,1926

As suggested above, not all German magic realist artists addressed modern life in this frank, polemical way, but magic realism shared with modernism more broadly "an attempt to find a new way of expressing a deeper understanding of reality witnessed by the artist [and writer] through experimentation with painting [and writing] techniques" (Bowes 2004: 9). The inclusion of Grosz and Dix into the magic realist fold illustrates how 'magic' was not perceived as a form of otherworldly mysticism, but more a mysterious sense of 'being' in the modern world, one that involved the darker aspects of human experience as much as a sense of awe and wonder. As Irene Guenther suggests, "The juxtaposition of 'magic' and 'realism' reflected . . . the monstrous and marvellous Unheimlichkeit within human beings and inherent in the modern technological surroundings" (1995: 36).

Although Roh's use of the term 'magic realism' for artists like Grosz and Dix was quickly replaced in German art history by that of 'new objectivity', the idea of magic realism spread out from Germany. In 1927 Roh's essay was translated into Spanish and appeared in the influential Revista de Occidente, a publication widely circulated in Latin America and read by writers like Jorge Luis Borges (Argentina) and Miguel ángel Asturias (Guatemala). Meanwhile in Europe, Roh's ideas excited the Italian writer Massimo Bontempelli (1878-1960), who founded the bilingual (French and Italian) magazine 900.Novecento in 1926 and who sought to explore the mysterious or fantastic aspects of reality, applied to the written word. Botempelli was an influence on the Venezuelan writer and diplomat Arturo Uslar-Pietri (1906-2001) who spent some time in Paris associating with avant-garde groups and who, following Roh's ideas, wrote stories in the 1930s and 1940s in Venezuela, exploring the mystery of people living amidst modern life. While Uslar-Pietri is an example of how Roh's ideas moved from Europe to Latin America, the literary genre associated with García Márquez is more indebted to a friend of Uslar-Pietri, the Cuban writer Alejo Carpentier (1904-80).

Like Uslar-Pietri, Carpentier spent time (1929-38) in Europe fraternising with the avant-garde. He warmed to Surrealism in particular, although later broke with the movement and returned to Cuba. Surrealism rejected 'realism' in art and literature: like German magic realists, Surrealists saw plain 'realism' as inadequate for conveying the mysteries and depths of reality. But unlike the German artists, who drew out this mystery through a focus on real-world objects, Surrealist championed 'the marvellous', which involved illuminating reality in unexpected ways through the free play of imagination. One aspect of this was using strange juxtapositions of objects, the most famous being, 'The chance meeting of a sewing machine and an umbrella on a dissecting table'. After Carpentier returned to Cuba, he suggested that in Latin America 'the marvellous' did not exist as some 'literary ruse', but was intrinsic to the continent's turbulent history, its fantastic geography and most importantly its strange mixture of magical and rational, mythic and pragmatic cultures (Native American, African and European). In the Prologue to his 1949 novel The Kingdom of This World, Carpentier coined the term 'marvellous realism' ('lo real maravilloso') to describe the type of literature which he saw as best expressing the inherently marvellous nature of Latin America. His novel combines concrete, real-world events—the slave rebellion in early 19th century Haiti—with the myths and magical practices of the African slaves. In creating this kind of literature, Carpentier was trying to distance himself from the European avant-garde and to create a distinctly Latin American form of modernism.

While 'magic realism' and 'marvellous realism' refer to somewhat different phenomena, a new term 'magical realism' emerged in literary criticism in the 1950s, influenced by a 1955 essay by the critic Angel Flores. Unlike Carpentier, who was keen to put a wedge between Latin American modernists and European writers, Flores emphasised the European precursors of what he termed the modern Latin American 'magical realists' such as Jorge Luis Borges, Rubén Darío and Julio Cortázar, who all combined fantastic and realist elements in their work. Flores identified European writers like Cervantes (Don Quixote) and Franz Kafka (Metamorphosis) as well as painters like Giorgio de Chirico as influential. Flores suggested that Borges, who drew on Kafka (and who was also probably aware of Franz Roh's ideas), was the pathfinder and moving spirit of this new Latin American magical realism. However, while Borges is recognised as a founding father of modern Latin American literature, his work is now seen as a precursor to magical realism rather than magical realist itself (Borges is difficult to define, but broadly he created fantasy worlds based on different philosophical truths to our own). So although Flores's term was to be widely adopted, his delineation of what it meant was not.

After the publication of Flores's essay, interest was rekindled in Carpentier's ideas and in those of magic(al) realism more broadly. This culminated in a new, vibrant wave of writing that has come to be known as the literary genre of magical realism and that includes novelists like Gabriel García Márquez (Columbia), Carlos Fuentes (Mexico) and Miguel ángel Asturias (Guatemala). The most notable qualities of this literature are the incorporation of magical events into a predominantly realist style of writing and the matter-of-fact depiction of magical happenings, something Salman Rushdie has astutely referred to as "the commingling of the improbable and the mundane". In García Márquez's One Hundred Years of Solitude, for instance, events like a man levitating after drinking hot chocolate or a girl ascending to heaven whilst hanging out the washing, are treated as if they are quite ordinary.

In political terms, Latin American magical realism emerged partly in response to the idealism engendered by the Cuban Revolution of 1959, which overthrew a brutal dictatorship and brought hope to millions across the continent. A new generation of writers, referred to as the 'boom writers', set out to create a form of writing that, while not denying European modernist influences, was distinctly Latin American in style and content. The novel One Hundred Years of Solitude (1967) was a landmark, a critical and commercial success which catapulted magical realism onto the international literary map. Subsequently, the genre has extended way beyond Latin America to include such eminent writers as Toni Morrison (US), Angela Carter (UK), Salman Rushdie (UK/India), Robert Kroetsch (Canada) and Ben Okri (Nigeria). What magical realism offers such writers is a narrative mode in which to explore alternative approaches to reality to those found in mainstream western thought or in literary realism. The character Saleem in Rushdie's Midnight's Children (1981) neatly describes this narrative mode as: "Matter of fact descriptions of the outré and bizarre, and their reverse, namely heightened, stylized versions of the everyday" (p.303). The term 'magical realism' has actually become far more popular than those of 'magic realism' or 'marvellous realism', and is now used widely by the public as well as by publishers, but some writers have begun to distance themselves from it, believing its popularity is reducing it to an ill-defined cliché.

To conclude, I want to offer a brief (and tentative) summary of the three terms explored here:

- Magic realism. A type of painting that emerged in 1920s Weimar Germany and was concerned with expressing, via a focus on real-worldly objects, the mystery of life that lurked beyond the surface of reality.

- Marvellous realism. A quality (argued to be) inherent to Latin American reality which finds expression in literature and relates to the complex mix of rational and magical, European and non-European cultures which coexist there.

- Magical realism. A literary genre that treats the extraordinary as something perfectly normal and incorporates magical happenings into a predominantly realist-style narrative.

A more detailed exploration of these terms, and the links between them, can be found using the references below.

References

Bowes, Maggie Ann (2004) Magic(al) Realism, London:Routledge.

Flores, Angel (1995 [1955]) 'Magical Realism in Spanish American Literature', in Zamora and Faris (1995).

Guenther, Irene (1995) 'Magical Realism, New Objectivity, and the Arts during the Weimar Republic,' in Zamora and Faris (1995).

Roh, Franz (1995[1925]) 'Magical Realism: Post-Expressionsism', in Zamora and Faris (1995).

Zamora, Parkinson Lois and Faris, Wendy (1995) Magical Realism: Theory, History, Continuity, Duke University Press.

Story Copyright © 2008 by Katy Wimhurst. All rights reserved.

Previous: The Image of the Lost Soul by Saki | Next: Book review by Tamara Kaye Sellman

About the author

Katy Wimhurst, who lives in Essex, UK, originally trained as a social anthropologist, but somehow ended up doing a PhD on Mexican Surrealism. She has a soft spot for magic, myth and mud. In a past life, she might have been Salvador Dali's moustache, and she'd like to be reincarnated as one of Russell Hoban's dreams. She writes fiction and non-ficion and has had stuff published in various magazines and online publications, including Guardian (Unlimited).

Katy Wimhurst, who lives in Essex, UK, originally trained as a social anthropologist, but somehow ended up doing a PhD on Mexican Surrealism. She has a soft spot for magic, myth and mud. In a past life, she might have been Salvador Dali's moustache, and she'd like to be reincarnated as one of Russell Hoban's dreams. She writes fiction and non-ficion and has had stuff published in various magazines and online publications, including Guardian (Unlimited).

Home

|

Competition

|

Privacy

|

Contact

|

Sponsorship